In the arts, practice is everything. I know this because I lived it. In college, I was a woodwind major, playing the saxophone. My life revolved around practice rooms. Hours of scales. Long tones until my lips were buzzing. Etudes, arpeggios, and drills over and over until the notes weren’t just learned, they were built into muscle memory. At first, it felt tedious. Repetition can wear you down. But eventually, the practice did what it was supposed to do: it freed me. My fingers no longer stumbled. My breathing fell into rhythm. I didn’t have to think about the mechanics anymore—I could focus entirely on the music itself.

That’s what practice does. It clears away the clutter between you and the art. And photography, though it might not seem obvious at first, works the very same way.

Most people assume photography is about two things: having “a good eye” and having a good camera. But just like the saxophone, your camera is an instrument. If you don’t know it intimately—every dial, every menu, every subtle shift in response then you’ll always be stumbling when the moment arrives. Shutter speed, aperture, ISO, focal length, white balance, exposure compensation, and post-processing decisions—these are your scales. They may not sound glamorous, but they’re the foundation. When you know them cold, you’re free to focus on the art rather than fumbling with the machine.

But here’s where it gets interesting. Just like with music, technical mastery isn’t enough. I knew players in college who could shred through the hardest passages flawlessly, yet somehow their music left you cold. They had technique but no soul. Photography has the same trap. You can produce images that are sharp, perfectly exposed, technically flawless—and yet, they feel lifeless. What sets a memorable photograph apart is vision.

Vision is the ability to see beyond the obvious. Where the average person sees only what’s right in front of them, the practiced eye sees possibilities. A patch of light falling across a brick wall becomes a composition. A child chasing pigeons becomes a story. A foggy morning transforms a parking lot into something mysterious. That ability to see doesn’t come from reading a manual. It comes from training yourself to notice, over and over, until it becomes second nature—just like the hours I spent noticing how breath and fingers worked together on the saxophone.

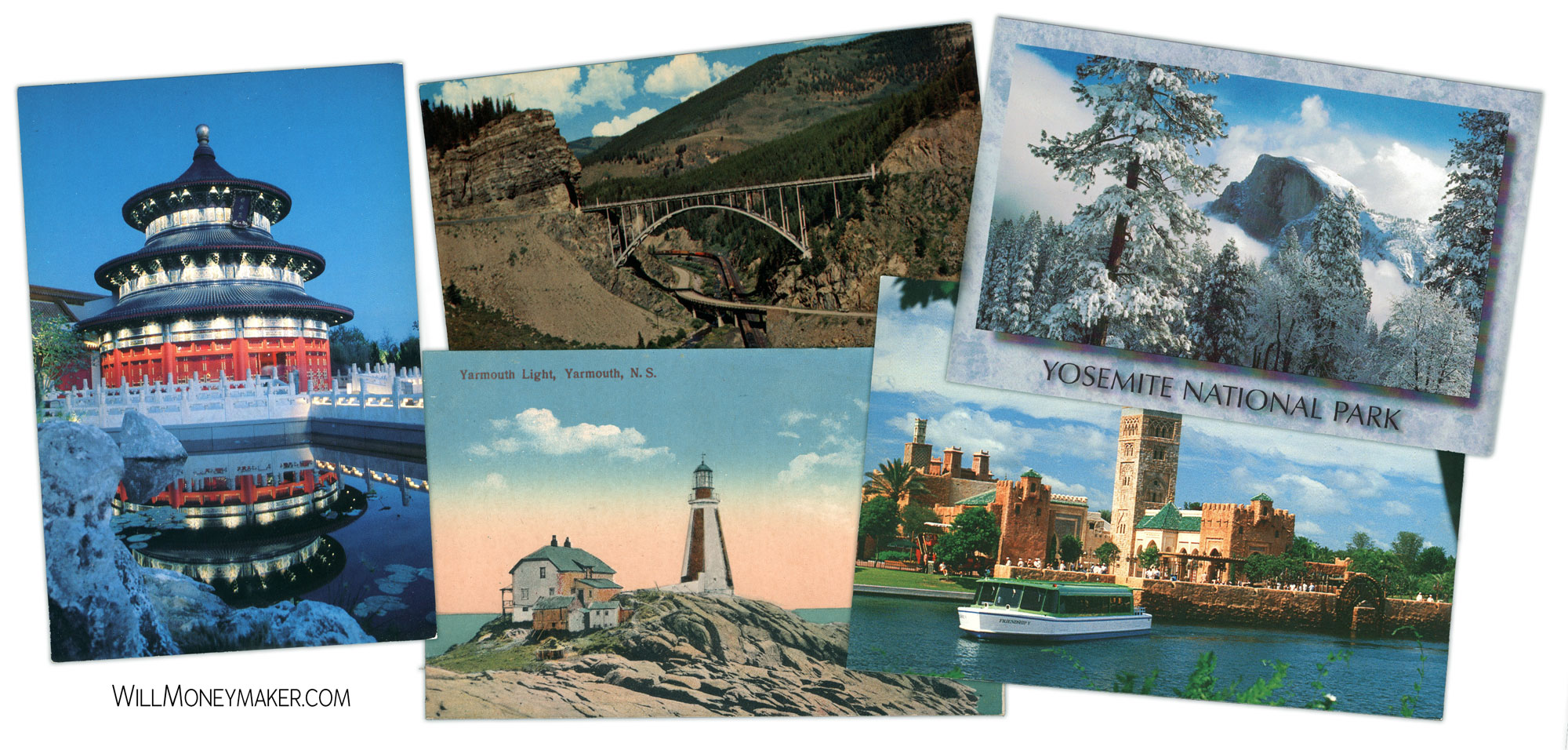

Landscape photographers embody this idea of practice beautifully. Many of them return to the same spot again and again. They’ll hike to the same overlook in spring, in autumn, at sunrise, in pouring rain, under a full moon. Why? Because they’re not just collecting shots. They’re practicing. They’re training themselves to see how a place changes, how light transforms it, how subtle variations reveal new possibilities. In music, you play the same piece repeatedly, not to get bored of it, but to discover new depth in it. Photography works the same way.

And here’s the thing: the technical and the creative feed each other in a loop. The better you know your instrument, the easier it is to translate vision into reality. The sharper your vision, the more intentionally you choose your technical settings to support it. It’s like jazz improvisation. Once the scales are under your fingers, you can bend and twist them into something unique in the moment. In photography, once you’ve drilled your camera skills, you can bend and twist light, shadow, and perspective into something only you would have seen.

So, how does a photographer actually practice? Let’s break it down in ways that mirror music practice.

Start with routine warm-ups. Sit with your camera at home and just run through settings. Change ISO without looking. Adjust aperture and shutter until you can feel the difference instinctively. Know your camera like a saxophonist knows their keys.

Then move to focused drills. Maybe dedicate a week to practicing motion blur cars passing, water flowing, people moving through the frame. Or spend a week mastering depth of field shallow portraits one day, sweeping landscapes the next. Just like a musician isolates problem areas, you isolate technical elements until they’re comfortable.

Add in observational practice. Take your camera for a walk and give yourself permission not to shoot. Just look. Watch how light falls across a building. Notice reflections in puddles. Pay attention to shadows at different times of day. This is like ear training in music—teaching yourself to notice nuances that most people miss.

Don’t forget review sessions. Musicians record themselves, then listen back critically. Do the same with your photographs. Look at your images from the past month. Which ones speak to you? Which ones fall flat? Ask yourself why. This reflection is part of practice, it sharpens your instincts for next time.

And finally, challenge yourself creatively. Jazz musicians improvise; classical musicians tackle new repertoire. Photographers can do the same. Try a theme, a restriction, or a project. Maybe commit to a week of only shooting at night, or only using one focal length, or only capturing shadows instead of subjects. These exercises stretch your vision and keep your creativity alive.

When you start seeing photography this way, it stops being about snapping a button. It becomes an art form driven by the same commitment, repetition, and curiosity that shape every other discipline. Practice makes you fluid. Practice makes you free. And when the mechanics fade into the background, your creative voice can finally step forward.

So yes, photographers absolutely practice. They need to. It’s the difference between taking a picture and making a photograph. It’s what transforms snapshots into art. And I can tell you from my saxophone days, the hours you put in aren’t about perfection. They’re about reaching that magical point where you’re no longer thinking about the instrument at all. You’re just expressing yourself.

And when that happens in photography when you pick up your camera and the settings flow naturally, when you frame instinctively, when you catch yourself seeing the extraordinary in the ordinary—that’s when you know you’re more than just clicking a button. You’re making art that lasts.