Photography looks ordinary now. A phone comes out, a tap happens, and an image appears. That ease can make photography seem like a simple act of collecting proof that something took place. Yet the real power of photography has never been only about proof. It has always been about attention, time, and meaning. A photograph can be a record, but it can also be a decision about what deserves to be noticed. It can be a way of saying, “This mattered to me,” even when the subject is small, quiet, or gone a moment later.

This essay argues three ideas. First, photography is a distinct way of seeing, not only a way of recording. Second, the emotional force of photography comes from its direct relationship to time and loss, plus the photographer’s choices. Third, the phone era did not erase photography. It changed the social conditions around it, which makes intention and care more valuable, not less.

What makes photography photography

Many arts involve interpretation, but photography has a strange physical link to the world. A photograph begins with light from a real scene hitting a light-sensitive surface, whether film or a digital sensor. Painters can invent a sunrise. Writers can invent a face. Photographers can invent in other ways, through staging, editing, and selection, but the starting point is still a light trace from something that stood in front of the camera at a particular time.

That link matters because it gives photographs a special kind of authority. People often trust photographs more than they should, and history is full of images used for propaganda, advertising, and deception. Still, the basic feeling remains. A photograph carries the pressure of “this happened,” even when the meaning is unclear. That pressure is why photographs move us in ways that feel different from drawings or stories. A photo can look like a message from time itself.

Yet photography is not the world. It is a slice, a framing, and a choice. The camera does not decide what is included, what is excluded, what is sharp, what is blurred, or what moment becomes the “real” one. The photographer decides. Even in casual phone snapshots, someone chooses a distance, an angle, a timing, and a subject. The technology can be fast, but the act still involves judgment.

So what makes photography photography is a blend of two forces that often pull against each other. One force is mechanical capture, the light trace from a scene. The other force is human intention, the choices that shape meaning. That tension is where photography lives.

A short history of the medium as a history of desire

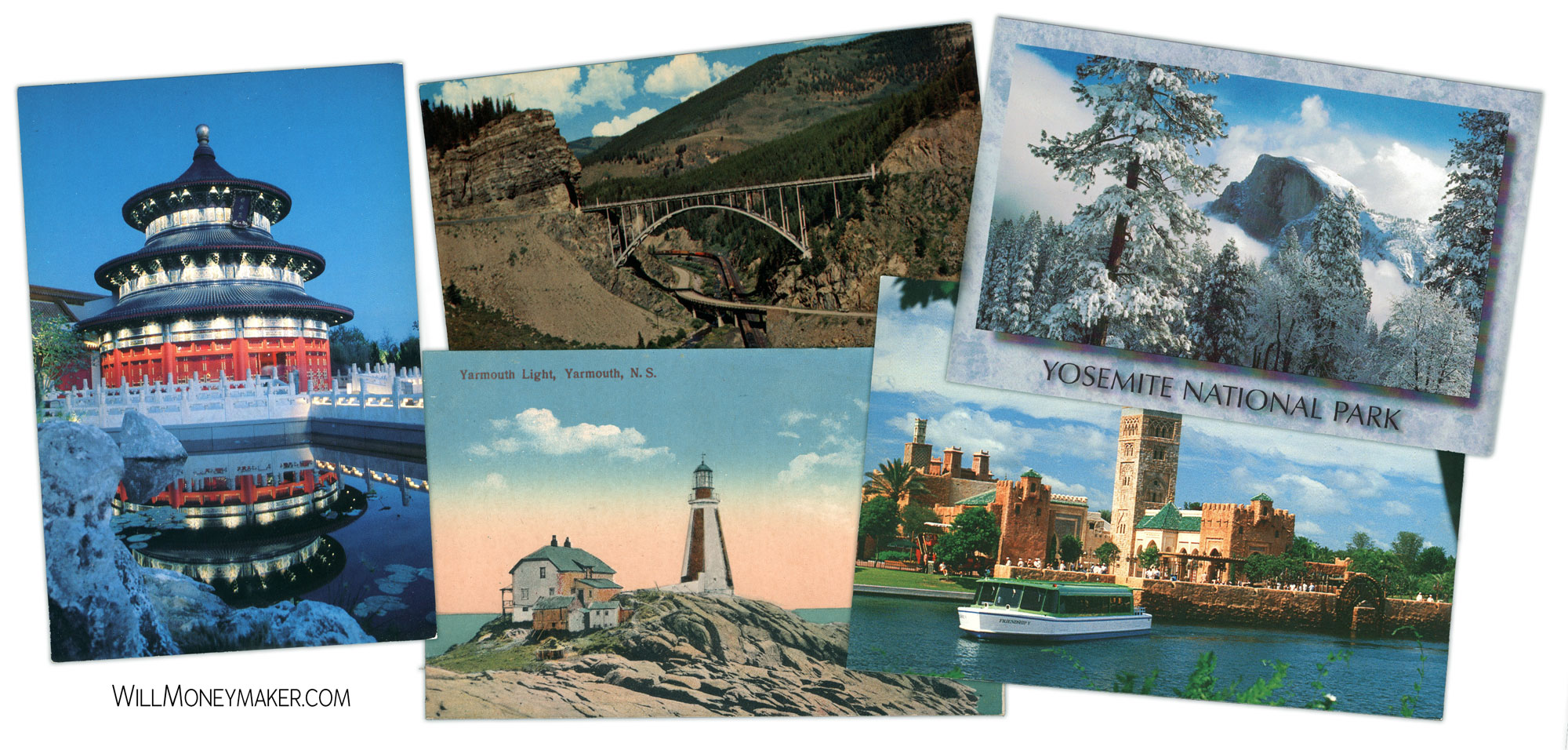

The early history of photography is often told as a story of invention. It is also a story of desire. People wanted images that lasted. People wanted portraits that did not require a painter. People wanted proof of distant places. People wanted to keep faces after death, and to keep moments after they passed.

Long before film, the camera obscura showed that light could project a scene onto a surface. That device was useful for artists, but it did not fix an image. The great shift came when inventors found ways to make light leave a stable mark. Nicéphore Niépce produced one of the earliest surviving photographs in the 1820s. Louis Daguerre announced the daguerreotype process in 1839, producing detailed images on metal plates. Around the same time, William Henry Fox Talbot developed a negative-positive process, which allowed multiple prints from one capture. That negative-positive idea became one of the central engines of photography for more than a century.

From there, the medium became faster, cheaper, and more portable. Wet plate collodion in the 1850s reduced exposure times and improved detail, though it demanded messy chemistry on site. Dry plates later removed much of that burden. Kodak’s roll film and the slogan “You press the button, we do the rest” shifted photography into everyday life. Smaller cameras and 35mm film made candid street photography easier. Color processes turned family albums into bright domestic archives. Digital sensors and memory cards removed the cost per frame, which changed behavior. Phone cameras made photography constant.

This history is not only technical. Each stage also changed what people thought photography was for. Early photography leaned toward portraiture, documentation, and status. Later it became a mass social practice, a family habit, and a form of journalism. It also became art. The museum world did not embrace photography quickly, partly because it seemed too easy, too mechanical, too linked to commerce. Over time, artists proved that the medium could carry complex ideas and personal voice. That debate never fully ended. Even today, some people treat photography as a lesser art because the camera “does the work.” That idea misses the point. The camera can capture light, but it cannot choose meaning.

The feelings of photography

People often say photography is about memory. That is true, but it is not the full story. Photography can create several kinds of feelings at once, including wonder, grief, pride, tenderness, and sometimes discomfort. The feelings come from at least four sources: time, attention, distance, and responsibility.

Time. A photograph freezes a moment, but it also announces that the moment is gone. This is one reason photographs can hurt and comfort at the same time. Roland Barthes wrote about this in Camera Lucida, describing how some images carry a piercing detail that strikes the viewer. He called that detail the punctum. You do not have to know the term to know the sensation. It is the tiny thing in an image that makes the scene feel alive and makes the loss feel real.

Attention. Photography trains attention. When you carry a camera, you start noticing light on walls, expressions that flicker for a second, and patterns that most people walk past. The act of looking becomes deeper. The scene becomes more specific. That practice can change daily life. It can make a walk richer. It can make ordinary places feel worth noticing. This is one reason many photographers describe photography as calming. The camera gives the mind a task: look closely, choose carefully, wait for the right moment.

Distance. A photograph is both close and distant. You can hold a photo of a person in your hand, but the person is not there. You can see a place you have never visited, yet you are still far away. That strange blend can create longing. Susan Sontag argued that photography can also turn the world into something consumed, collected, and possessed. She was not wrong. A camera can become a tool for taking without caring. Still, distance can also create empathy. A well made photo can make another person’s reality feel vivid.

Responsibility. Photography involves power. Pointing a camera at someone is not neutral. Publishing an image can shape how others are seen. Documentary photography, war photography, and street photography all raise questions about consent, dignity, and context. This ethical side is part of what makes photography serious. A photographer is not only a viewer. A photographer is a translator, and translators can be honest or careless. The medium invites us to ask: What am I showing. What am I hiding. Who benefits. Who gets harmed.

When photography is done with care, these feelings can coexist. The result can be more than a pleasing image. It can be an encounter.

Why phones did not end photography

Phones did not destroy photography. They changed its scale and its social meaning. Three shifts matter most.

First, the volume of images exploded. When images are endless, a single image can feel cheap. That changes how people value photographs. In earlier eras, a family might have a few dozen portraits that marked major events. Now people may take hundreds of photos at one gathering, and never look at them again.

Second, photography became tied to performance. Social media turned images into signals. A photo can be a way of saying “I was here,” “I am doing well,” “I have good taste,” or “Look at me.” That can drain sincerity from the act. It can also push people toward trends and away from personal seeing.

Third, the tools became smarter. Computational photography can brighten shadows, sharpen faces, smooth skin, blur backgrounds, and assemble multiple frames into one. These features can be helpful. They can also make images feel less connected to a single moment. The line between capture and construction is now blurrier for everyone, not only for professionals.

None of these shifts erase photography. They create a new challenge. In the phone era, the value of a photograph depends more on intention. A meaningful photograph is one that was made on purpose, not only taken.

This is the core reason you might love photography, even if you already take photos every day. Loving photography is not the same as owning a camera. It is choosing to treat seeing as a craft.

What deeper photography looks like in daily life

Going beyond the basics is less about technical complexity and more about commitment to a way of looking.

It can mean slowing down and waiting for light that tells the truth of a place. It can mean returning to the same subject across months or years, building a body of work rather than a pile of files. It can mean printing images, because prints change how you judge a photo. On a screen, everything scrolls past at the same speed. On paper, a photo has weight, size, and presence.

It can also mean accepting limits. Many great photographers worked within strict constraints, like one lens, one format, one neighborhood, one theme. Limits can free the mind. They reduce options and increase attention.

Most of all, deeper photography means caring about what the image says. Every photograph has content, and every photograph has form. Content is the subject. Form is how the subject is shown, including light, framing, focus, timing, and tone. Two people can photograph the same street corner and produce images that feel nothing alike. That difference is the photographer.

Why you should care

Photography is one of the few practices that can be both artistic and practical at the same time. It can help you notice your own life. It can help you see other people more clearly. It can help you record what matters before it disappears. It can also build patience and curiosity, because good photographs often require waiting, returning, and trying again.

The phone era makes this practice more available than ever. You do not need permission to begin. You do not need expensive gear to learn how light behaves. You do not need a studio to make images that carry emotion and meaning. The challenge is not access. The challenge is intention.

Photography becomes something you love when it stops being only about what is in front of you and starts being about how you relate to what is in front of you. A camera, even a phone, becomes a tool for attention. Attention becomes a habit. That habit changes how the world looks.

References for readers who want to go deeper

Barthes, Roland. Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography. 1981.

Benjamin, Walter. The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction. 1936.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Photography: A Middle Brow Art. 1965.

Sontag, Susan. On Photography. 1977.