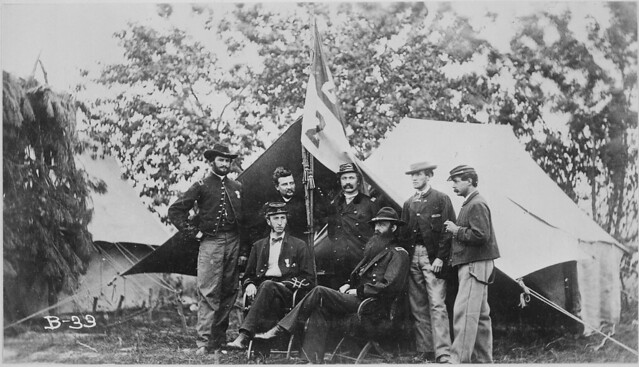

Mathew Brady (1822-1896) was a photographer whose work is quite well known and famous today. In addition to taking photographs of 19th-century politicians, who we would otherwise have no images of except in paintings, he also documented the American Civil War in photographs. The Civil War is the first war to be documented and disseminated to the public via newspapers using photographic accompaniment. Mathew Brady, one of his many personally trained assistants, took most of those photos.

He and his assistants marched across the country during a very dangerous time for travel, searching for the most compelling, truthful images of the war. Amongst them, they took more than ten thousand photographs of the war, letting the average civilian American see in real, graphic detail just what was happening to the men on the nation's battlefields.

Those images were important to the American public. Without them, most Americans who weren't in the fray relied on letters from loved ones who were in the military to describe the war. Naturally, most men wouldn't want to overly concern their wives, mothers, daughters, and sisters, so often downplayed just how difficult conditions were and how gory the conflicts between North and South could be. With Mathew Brady's photographs appearing in newspapers across the country, people could see the truth for themselves, and it motivated quite a few civilian groups to form to give supplies and relief to the soldiers in different ways.

Because of his work and because photographing war in progress was an entirely new thing, Mathew Brady gave a more defined structure to the role of photographers as historians. By documenting modern life in photographs, photographers were creating valuable historical resources for future generations to use to understand the past and know what it was like with more intimacy than a painting could provide. Because of him, photography became a powerful tool in the world, not just for family photos, but in politics, society in general, and the culture of the times and places in which the photographs were taken. This is still true of photography today, in the digital era.

Louis-Jacques-Mandé Daguerre officially invented photography in 1839. That is the same year Brady left his home in upstate New York and his Irish parents to come to seek his fortune in New York City with so many others. He worked briefly in a department store as a clerk and then made jewelry cases, including those in which early photos, called daguerreotypes, were displayed. In 1844, he decided to get in on the photography craze and opened his own studio and the corner of Broadway and Fulton. As an expert marketer, Brady was soon recognized and sought after as one of the best-known photographers of the era, attracting high-profile clients.

He was even mentioned in the first issue of the new Photographic Art Journal in 1851. The article on him in the journal described Brady as a “fountainhead” of the new photography business. He also won a gold medal in a prestigious photography contest in London that year. Interestingly, the other two winners in that contest were also American photographers. He expanded his business to include paper prints and daguerreotypes, moved his studio into a more luxurious one, and even opened a second studio in Washington, D.C. In this location, he attracted prominent politicians, and his famous 1860 photograph of Abraham Lincoln was instrumental in making Lincoln a more famous and recognizable figure nationwide. Brady's photographs began to influence current events, which increased his reputation and desirability among the elite as a photographer.

When the Civil War started, Brady saw an opportunity to document the war in photographs for all Americans. He assembled a group of photographers he trained and sent them out following the armies on both sides of the conflict. Not only are the photographs produced as the first photographic documentation of war, but they are also the first photographic documentation of any major historical event. Brady invested a ton of money into this venture from the private fortune he had accumulated as a top “celebrity” photographer.

However, even though his photographs of the war were widely published, he never made the money back he invested in the project. Newspapers couldn't afford to pay him what he needed to recoup his financial losses. As a result, he became nearly destitute after the war, without even enough money to continue operating a prestigious photography studio. Without even one nice studio to his name, his fame rapidly disappeared following the war, and he was never the go-to name in high-profile photography before the war began.

Though his work in photographing the war practically bankrupted him, it made him famous to future generations. This is because his Civil War photographs became a part of the national archives and gained a reputation as the best source for visual information about the mid to late 19th century and the Civil War. Scholars revived their interest in his work in the 1930s during the work of the Civilian Conservation Corps in documenting the history of photography and the Civil War itself. His work greatly influenced those who were using photography to document the Great Depression. Mathew Brady was their inspiration.

Today, Mathew Brady is once again the famous photographer he was before he began his Civil War photographic documentation project. He would likely be very happy to know his name, fame, and excellent reputation live on among photographers and historians. He provided something unique to history… the photographic documentation of war and the distribution of those photographs to the public while the war was happening. His name will always be in American history because of that valuable project.