Born May 26, 1895, Dorothea Lange was to become one of the most famous photographers of the Great Depression in America. Her photographs most accurately capture the true human devastation this economic disaster wrought on our nation. Before her photographs began appearing in contemporary publications, the Great Depression was, to most people, something they only read about in newspapers and magazines and their own personal experiences with it. Dorothea’s photographs made the Depression a human event that everyone could understand. They also helped usher in the new art of documentary photography and made her one of its pioneers.

Her parents were the children of German immigrants, and she was born and raised in Hoboken, New Jersey, along with her younger brother. Her early life was the same as most children of the era until she contracted polio at age 7. While she survived it relatively unscathed, it did weaken her right leg, which left her with a lifelong limp. She was teased for it, and she later described the limp as both a bad and good force in her life, as enduring the teasing helped to shape her character and made her stronger emotionally and in her determination to do the things she wanted to do.

Her childhood continued as normal as it was after that until her father abandoned the family when she was 12. After this traumatic event, she changed her name from Dorothea Margaretta Nutzhorn to Dorothea Lange, dropping her middle name entirely and abandoning her father Heinrich’s surname for her mother Johanna’s maiden name. This was her way of showing that she had abandoned her father as much as he had abandoned her.

She attended the Wadleigh High School for Girls, then attended Columbia University in New York City, where she studied photography under the tutelage of Clarence H. White. While studying, Dorothea informally interned at several photography studios in New York City. Upon graduation, she traveled on what was to be an around-the-world trip in 1918, accompanied by a female companion. They were robbed in San Francisco and forced to abandon the rest of the trip. Dorothea stayed there and got a job as a photofinisher. She opened her own successful photography studio the next year and moved across the bay to Berkeley, where she lived for the rest of her life.

While operating her photography studio, Dorothea met and married Maynard Dixon, a respected painter of western scenes, and had two sons with him, one born in 1925 and one born in 1930.

When the Great Depression began, Dorothea became interested in what was going on in the neighborhoods and streets and began taking more photographs there than in the studio. She was particularly interested in homeless and unemployed people, and her photographing them landed her a job with the Federal Resettlement Administration, later known as the Farm Security Administration.

She divorced Maynard Dixon in 1935 and quickly remarried Paul Schuster Taylor, an Economics professor at the University of California at Berkeley. They began exploring the Great Depression together, documenting the poverty it wrought on rural farm workers, sharecroppers, and migrant laborers. Dorothea took the photographs while Paul gathered and compiled the economic data. They did this project together for the next five years until the Great Depression ended with President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. Dorothea’s most famous photographs were taken during this time period and a little before, beginning in 1933.

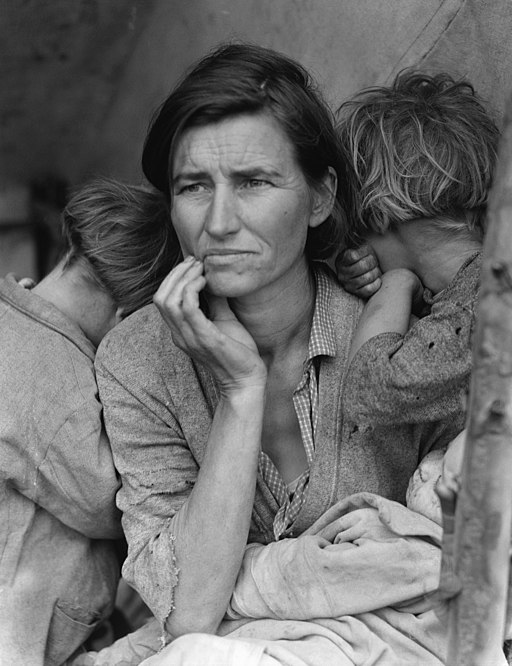

Many of her photographs became iconic images of the Great Depression that are still famously associated with that time in American history. As she was taking them, she submitted them for free to newspapers across the country, which brought more public attention to the plight of the people hardest hit by the Depression. Her most famous photograph, Migrant Mother, actually helped save lives.

Migrant Mother is a picture of a starving mother with her two children in a migrant camp. Dorothea later said the woman in the picture asked her no questions about why she was taking pictures, and Dorothea provided no answers. Because of the silence, she got five really good quality exposures, one of which became the iconic image of the Depression. It was only after she took her photos that the two women talked.

Florence Owens Thompson was 32 years old and told Dorothea that she and her children had been living on vegetable scraps from the fields and birds her children killed and that she had just sold the tires on her car to buy food. They lived in a tent. Dorothea sent two pictures of Florence and her children to her editor at a San Francisco newspaper, and the editor, in turn, told federal authorities about conditions in the migrant camp where Florence lived. An article was published about the camp with the pictures Dorothea took, and the federal government rushed aid to the camp to keep the people there from starving.

While Dorothea is best known for her Great Depression photography, she gained some secondary fame by photographing the evacuation and internment of Japanese Americans into camps during WWII. She even gave up her 1941 Guggenheim Photography Fellowship to follow those forced into the camps.

Her photographs were so clearly critical of the government policy toward Japanese Americans that the Army impounded most of them, and the public did not see them until after the war. Today, they can be seen in the National Archives website’s Still Photographs section.

Later, Dorothea became a faculty member at the California School of Fine Arts very first Photography department and co-founded her own magazine, Aperture, in 1952. She focused much of her work in Aperture to the plight of poor and displaced people, highlighting the injustices they faced in America.

Dorothea died in 1965 at 70 and was survived by her husband Paul, two children, three step-children, and many grand and great-grandchildren. She was inducted into the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 2003, an elementary school in Nipomo, California (near where she photographed Migrant Mother) was named after her in 2006, and in 2008, she was inducted into the California Hall of Fame.