When we look at old photographs, we tend to expect them to be in black and white. We expect the past to feel distant, muted, and quiet, as if history were always supposed to be sepia-toned and far away.

Sergei Prokudin-Gorsky did not accept that.

He wanted people to see the world as it actually looked. Not in our time, but in his. Not as a ghost of history, but as something alive with color.

He was born in 1863 into a world that respected both art and science. That detail matters because his whole life sits right at that crossroads. He did not choose just one lane. He studied chemistry and the arts, including painting and architecture. That mix, the practical and the creative, gave him the kind of mind that asks, “What if this could be better,” and then goes and proves it.

His education took him from Saint Petersburg to Berlin and Paris, where he sharpened his skills under prominent scientists and artists. So when he came back to photography, he brought more than curiosity. He brought tools, training, and a mindset that could treat an image like both an experiment and a work of art.

Now, at the turn of the century, photography was moving fast, but color photography was still more dream than everyday reality. People were experimenting, but most methods were unreliable. Results could be inconsistent, and the colors could fade or fail. It was not the kind of thing you could count on if you wanted to document a whole world.

Prokudin-Gorsky looked at that problem and aimed higher.

His solution was bold, but also beautifully systematic. He took three black-and-white photographs of the same scene, each through a different filter: red, green, and blue. Then he combined those three images into a single color photograph. That approach, called color separation, produced color with a level of accuracy that people at the time were not used to seeing.

And this is where it stops being just a technical story and becomes a story about history.

Because Prokudin-Gorsky did not want to use this process only for a few portraits or studio scenes, he had a larger idea. He wanted to document the Russian Empire in color.

In 1909, he brought that idea to Tsar Nicholas II.

Picture that moment for a second. A photographer stands before the Tsar and says, in effect, “I want to capture this entire empire in color.” That is a big proposal. It is expensive, it is complicated, and it is ambitious in a way that borders on impossible.

The Tsar was impressed. He supported the project. And he gave Prokudin-Gorsky a specially equipped railroad car, complete with a darkroom. That one detail, a railroad car with a darkroom, is like handing a painter a moving studio on wheels. It gave him the mobility to go where he needed to go and the ability to process his work as he traveled.

From 1909 to 1915, Prokudin-Gorsky became a traveler with a mission. He moved across vast distances, documenting a world that was still standing, but also heading toward major change.

His photographic journey through Russia became a kind of visual chronicle. He captured the architectural splendors of old churches and monasteries. He captured the rugged beauty of the Ural Mountains. He captured the everyday life of rural villages. He captured the diverse peoples of the empire, not as stereotypes, but as real individuals, present and human.

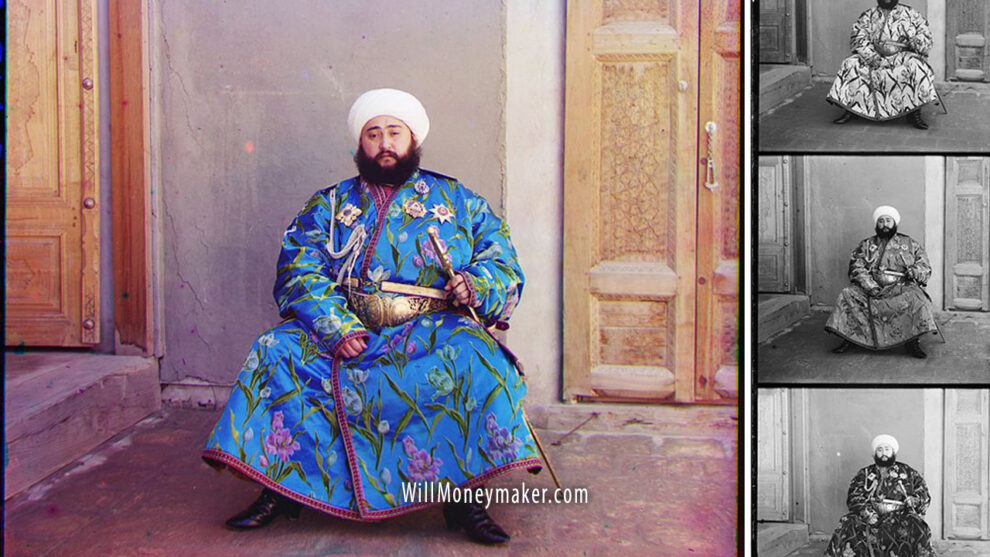

One of his most famous images is the portrait of the Emir of Bukhara, taken in 1911. It is iconic for a reason. In color, the scene hits differently. It carries an immediacy that black and white rarely delivers in the same way, especially for viewers who are separated from the subject by time and distance. Color does something strange and powerful. It reduces the emotional gap. It makes the past feel closer.

Through his lens, people of his era could see a multifaceted Russia, vivid and detailed, and that helped shape a deeper appreciation for its complexity and diversity.

And his project did more than create beautiful images. It showed what color photography could do for historical documentation. It added realism, and it made history feel tangible. It was no longer only a record of shapes and shadows. It was a record of a living world.

In that sense, Prokudin Gorsky was doing more than taking pictures. He was building a visual archive that could carry memory forward with startling clarity.

But history has a way of interrupting even the grandest plans.

World War I began, and then the Bolshevik Revolution followed. Those events brought an end to his major project. In 1918, Prokudin-Gorsky left Russia. He eventually settled in Paris. He continued working, but on a smaller scale. He would never again take on something as sweeping as his survey of the Russian Empire.

He died in 1944, but the importance of what he did did not die with him.

Today, his photographs stand as a historical archive, and they also stand as evidence of what happens when a person combines scientific precision with artistic sensibility. In a digital age where images are everywhere and often forgotten seconds after we see them, his work pushes us to notice the craft behind each shot. Each photograph was not a casual click. It was a careful process, planned and executed with intent.

He showed us that the intersection of art and science is not some abstract concept. It can be practical, and it can be beautiful. It can change what people think is possible.

And that might be the most lasting part of his legacy. Not only the images, but the way of seeing. Curiosity paired with technical skill, guided by a belief that photography could capture and communicate the human condition.

Prokudin-Gorsky did not just document a world. He preserved it in color, so that long after the moment passed, we could still see it with our own eyes, one frame at a time.