Photography has this rare ability to tell a story, to let us glimpse into worlds we might otherwise never see. And few photographers did that quite like Lewis W. Hine. For anyone who loves photography, Hine’s work is a testament to how powerful an image can be. He wasn’t just taking pictures; he was documenting history, sparking reform, and, most importantly, giving a voice to people who were often invisible in society. His images of immigrants, child laborers, and industrial workers helped change laws and inspired generations of photographers to use their craft for something greater.

Early Life and Family: Seeds of Empathy

Hine’s journey started in Oshkosh, Wisconsin, where he was born on September 26, 1874. Growing up, he was surrounded by the values of hard work and resilience. His father, Douglas Hull Hine, was a Civil War veteran who worked as a farmer and later in a small store. Tragically, when Lewis was just 18, his father died in an accident, a loss that forced him into adulthood and responsibility sooner than most. With limited resources, Hine began working to support his family, taking any job he could find.

Hine’s mother, Sarah Hayes Hine, was a deeply compassionate woman and an educator. She instilled in him a love for learning and a strong sense of empathy that would become the foundation of his photography. Sarah’s influence was subtle but profound; she nurtured a sensitivity in Hine that, years later, would be visible in his compassionate portraits of children, workers, and immigrants. Hine’s early life wasn’t easy, but it shaped him into someone who didn’t just look at the world; he saw it deeply and felt it personally.

Finding Photography and a Mission

Despite the hardships, Hine pursued his education passionately. He attended the University of Chicago, then took courses at Columbia University and New York University, all while working various jobs to support himself. It was while teaching at the Ethical Culture School in New York City in 1901 that he first picked up a camera—and he never looked back. Photography became a way for him to combine his love for education and his drive for social justice.

One of Hine’s first major projects was documenting the experiences of immigrants arriving at Ellis Island. Between 1904 and 1909, he took countless photos of families, men, women, and children who had left everything behind in hopes of a new life in America. One of his most famous images from this period, Looking for Lost Baggage, Ellis Island, 1905, captures a mix of emotions—hope, anxiety, curiosity—in the faces of immigrants waiting to claim their belongings. For Hine, these weren’t just pictures. They were stories of courage and resilience, and he captured them with an empathy that shines through, even over a century later.

Shining a Light on Child Labor

For Hine, photography was never just about art; it was about making a difference. In 1908, he became the staff photographer for the National Child Labor Committee (NCLC). At the time, child labor was widespread, and many children were working long hours in dangerous conditions. Armed with his camera, Hine traveled across the United States, often going undercover to access factories, mills, and coal mines. Disguised as a salesman or inspector, he captured haunting images of children as young as eight years old working in filthy, unsafe environments.

These photographs are unforgettable. In one, a young boy stands covered in coal dust, his small frame almost swallowed by the oversized tools he’s expected to handle. In another, young girls operate heavy textile machinery, their expressions a mix of fatigue and resignation. Hine’s goal was clear: he wanted the public to see what he saw, to be as moved as he was by the plight of these children. His work directly contributed to changing child labor laws in the U.S., proving that photography could be a powerful tool for social reform.

Documenting Industrial America

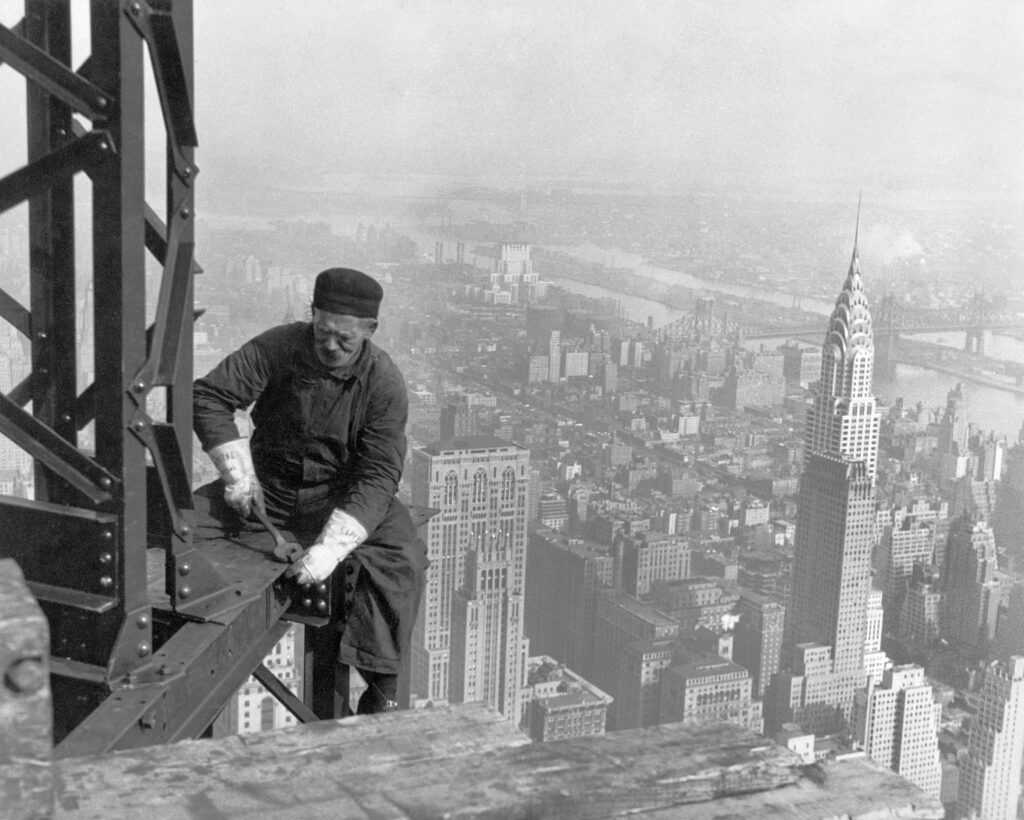

After his work with child labor, Hine continued to document the lives of working Americans, especially as the country faced the hardships of the Great Depression. His images of industrial workers highlight their resilience and skill. One of his most famous series features construction workers on the Empire State Building. Hine captured breathtaking shots of men balancing on steel beams hundreds of feet above the ground, often without safety harnesses, their faces a mix of calm and focus. It’s hard not to feel a sense of awe looking at these images—both for the courage of the workers and for Hine’s ability to capture their strength in such a raw, human way.

One of the reasons I think Hine’s work resonates so deeply with photographers today is because he didn’t just take pictures of people; he connected with them. He saw them as individuals, not just subjects, and that perspective comes through in every photograph. His portraits of workers and immigrants are filled with dignity, even when the conditions around them were anything but.

Hine’s Legacy: Lessons for Photographers Today

Hine’s work teaches us that photography can be so much more than a captured moment. It can be a call to action, a tool for empathy, and a way to connect with stories that might otherwise be forgotten. His images remind us of the power of compassion in photography—the way a photograph can make us feel something, make us see people as individuals with their own struggles and triumphs.

For photographers and anyone interested in history, Hine’s legacy is a powerful reminder that our craft can be a force for good. We can capture not only the beauty of life but also the difficult truths, the moments that need to be seen and remembered. Hine’s work continues to inspire generations of photographers to use their cameras with purpose, to see their subjects with empathy, and to believe in the power of a single image to change minds and even laws.

So, the next time you’re out with your camera, think about Lewis Hine. Think about his quiet determination to show the world as it really was, to make a difference with every click of the shutter. It’s a legacy worth carrying forward.